Making Sense of Atlanta and This Asian-American Moment

|

| I recall a night from my preteen years, before the crisis of self-awareness sets in and rattles your very identity. My family is out to dinner. My parents, who emigrated from South Korea before I was born, had embraced all things American with a certain jingoistic fervor, and that evening we went out to a Pizza Hut in the suburbs of Long Island. This is the late ’70s. |

| Waiting to be seated, it became clear we were being ignored. Several patrons who entered after us were immediately given tables. My father asked to speak to the manager, and with a raised voice he asked why we hadn’t been offered a seat. The manager, who looked to be a teenager, sized up my father’s evident rage and sighed. He pointed to a booth and we sat down. As the waitress handed us menus, she looked befuddled, almost as if to say, “I guess we’re doing this?” |

| Our order took forever, far longer than those who came after us. When the food finally arrived, it was burned to a crisp. My parents were livid. My younger sister and I sensed a pending calamity, and we slumped lower in the booth. |

| The tin fury in both my parents’ voices rang through the restaurant. My father pointed to the charred circle of dough and cheese and said, “This is how you serve us!?” He screamed about being mistreated, that — and here it came, the word — this was “racist.” Everyone stared. A man at the table next to us told my father to simmer down. The manager protested. Then he took a jab. We were “difficult customers from the start,” he said. My father’s face, normally a deep shade of brown, a peasant brown, turned red. He stood up, looked at my mother, my sister and me and said we were leaving. |

![]() |

| Six of the eight victims of the shooting in Atlanta. Top row from left: Yong Ae Yue, Hyun Jung Grant and Suncha Kim. Bottom row from left: Soon Chung Park, and Delaina Ashley Yaun and Xiaojie Tan. |

|

| I couldn’t look at anyone, including my parents. But when we got into the car, I yelled at my father about why he had caused such a fuss. Until that moment, we had been blissful citizens of the suburban middle, the pleasant, hidden center. Now, somehow, my father’s outburst had cracked open our very place in this universe. We were, all of a sudden, outsiders. Nonparticipants. Other. (The truth, I soon learned, is that we always were.) |

| He turned around and looked at my sister and me. “What they did was wrong,” he said firmly. “That’s not how we should be treated. I want you to remember this and whenever something like this happens, you have to say something. Don’t ever keep quiet. You have to fight.” |

| I looked away. I was starving and upset. But more than that I was unsettled about who I was, of my place in the collective, such as it was, which at the time meant the mostly white enclaves of an outlying district of New York City in the twilight of the 1970s. |

| In the tale of race relations, it’s a minor incident, perhaps a handful of words in a saga dominated by two massive ruptures in the founding of this country: the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement and continued killings of Black Americans. |

| But when I got to college and found my Asian-American cipher, I discovered just how rare that moment was. My friends’ parents didn’t always make a fuss. That’s not to say they didn’t know when they were being mistreated. But immigrants often don’t report such incidents, or rage at racism. Many are undocumented. Many don’t speak English. My father had the advantage of speech, citizenship and a rare ethnic disposition all Koreans will recognize as an anger incarnate (that’s another essay). |

![]() |

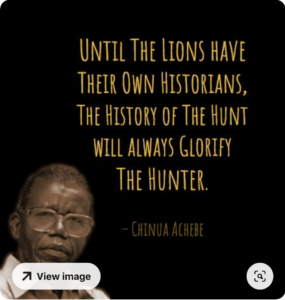

| Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American, who was beaten to death by two auto workers who apparently believed he was Japanese in 1982.United Press International |

|

| For decades, Asian-Americans have come together only in moments of crisis. The killing of Vincent Chin, for example. And now, the killings in Atlanta. We’ve always been a fractured state. We speak different languages, worship various religions, are politically diverse (or divided) and have the largest wealth gap in the nation. We are a phantom identity. |

| Even the rise in violence against Asian-Americans over the past year — tied to the pandemic and Donald J. Trump’s use of a frequent refrain: “the China virus” — has been cast into doubt as a unifying moment. Before the Atlanta killings, the writer Jay Caspian Kang made the case that it wasn’t entirely clear that there had been an actual surge in anti-Asian crimes or that Mr. Trump somehow was the trigger, especially as some of the suspected perpetrators were Black. He fails to consider the possibility that even non-Trump supporters might buy into his rhetoric and blame Asian-Americans for the pandemic. If we exist only in times of friction and we can’t even agree on a signal moment of brutality, do we exist at all? I mean, what are we fighting? |

| In a February essay, the writer Hua Hsu said, “It’s difficult to describe anti-Asian racism when society lacks a coherent, historical account of what that racism actually looks like.” Our “victimhood,” as he describes it, lacks a vernacularThe killings in Atlanta — six of the eight victims were Asian women— would seem to offer a trenchant record, even carve the words “anti-Asian violence” onto a granite stele as a kind of universal marker from which the rest of the world could learn. But no, the motive is officially undetermined. The Atlanta Police Department, citing the perpetrator’s words, attributed his violence as an attempt to rid himself of his temptations. The suspect, an evangelical white male who had a “sex addiction,” put a bullet in the faces of several of the women. |

| Even the outpouring of protests, the words of President Biden and the latest headlines describing the rise in anti-Asian attacks seem to have been cast in parallel to Atlanta. The yawning gap between the official record and the distress Asian-Americans feel in their bones is mind-numbingly frustrating. It’s exhausting. It also mirrors the stunted, disconnected aspect of the Asian-American identity itself. We seem to phase in and out of existence, often at the mercy of other people’s doubt. |

| Atlanta quashed any wavering among Asian-Americans. In the last few days, I’ve received emails and texts from my Asian-American friends, some whom I hadn’t heard from in years, asking, telling in some variation: “Hey, I’m here. You OK?” like a Bat signal. |

| But there is still a deep history of silence among Asian-Americans, of keeping out of the way. It’s partly cultural, but it’s driven more by a white narrative that submission, that following the rules, or not making a fuss, will get you ahead. It was given a name by President George Bush: “model minority.” |

| Despite the potent events behind Atlanta, I worry we will once again check out after some time has passed. Already the conversation has shifted after the killings in Colorado, which occurred less than a week after Atlanta. |

| And so, I will always return to how my father perceived that night. He decided to turn an uncivil moment, an episode of racism, into a real thing simply by giving it a name. He spoke it into existence. Only as an adult did I recognize that his outburst was in fact a brave act of creation. It forced me to acknowledge my difference, my distance from the false center I thought I inhabited, and gave me an identity. |

| But as we drove away, I heard something else, a moment of doubt. Mumbling under his breath, my father said, “I don’t know, maybe I made a mistake.” |

| [Read the rest of the essay here.] |

Social Qs: How to Check In With Asian-American Friends

|

| A reader wonders whether it’s appropriate to check in on a former colleague who is Asian-American after a year of targeted violence. |

| Since the beginning of the pandemic, I have been shocked by the amount of racist political language aimed at Asian-Americans and the spike in hate crimes against the community. As a white person, I feel ashamed that I didn’t focus on this problem sooner. During this period, I have often thought about a Korean-American woman I worked with several years ago. We grew close and moved our friendship beyond the office (dinners with our partners and theater evenings, etc.). I’d like to check in with her now and express my support over recent events. But it’s been several years since we’ve been in touch, and something is holding me back. What do you think? |

| I don’t want to sound harsh here. Your heart is in the right place, and expressions of support can often bring comfort to those who are suffering. But if you haven’t been in touch with your friend in years, contacting her now may seem more like racial profiling to her — “Hey, I know an Asian-American!” — than personal support. |

| Calling or writing out of the blue may also be burdensome to her now. Last summer, during the Black Lives Matter protests, I heard from several Black readers that the volume of well-meaning overtures they received from white people they hadn’t spoken to in ages felt overwhelming at a time when they were traumatized and exhausted. |

| Now, this is not an argument against rekindling old friendships. Just do it when the impulse is centered on your friend (or your shared history), not current events. In the meantime, focus on actions you can take to help the Asian-American community, like educating yourself about the history and current circumstances of violence and racism, volunteering, supporting local businesses, or donating to anti-violence organizations. “Thoughts and prayers” are great, but there’s hard work to be done, too. |

|